The rain starts as a polite mist and turns, inevitably, to sideways needles. Your jacket beads water beautifully. Your legs are damp but coping. Yet by the second climb, there it is: the clammy chill down your spine, the slow creep of wet sleeves from the inside out. You stop, unzip, and steam billows out like you’ve been poaching yourself.

Most hikers blame the forecast, the brand, or the “British weather”. The real culprit is quieter: the way we wear waterproofs. Zipped to the chin, over the wrong layers, at the wrong time, many rain‑coats trap sweat faster than they shed rain. The result feels like a leak, but it’s you.

The twist is that outdoor guides, who spend far more hours in foul weather than weekend walkers, almost never hike like this. They manage temperature first, rain second. The difference is small choices that keep them dry from the inside out, even when the clouds refuse to cooperate.

Why your “waterproof” leaves you soaked from the inside

A modern rain jacket is a barrier. Water from the outside can’t get in; that’s the point. But your body is constantly pumping out warm, moist air. If that vapour cannot escape faster than you’re producing it, it condenses on the inside of the fabric and on your clothes. That “leak” is often just your own sweat, cooled.

Breathable membranes (think Gore‑Tex and friends) help, but they’re not magic. They work best when:

- There’s a temperature difference between inside and out.

- You’re not pushing them past their limits with full‑tilt effort.

- The outer fabric isn’t saturated and clogged with dirt or old DWR.

The classic mistake is pulling on a fully waterproof, non‑breathable or tired old shell at the car, zipping it to the top, and marching uphill in a cotton t‑shirt. Cotton holds sweat like a sponge. No venting, no wicking, just heat and moisture building until the inside of your jacket feels like the walls of a tent at dawn.

“Most ‘leaky’ jackets I’m shown aren’t leaking at all,” says Anna Reed, a Lake District mountain leader. “They’re doing exactly what they’re told: keeping rain out. It’s everything underneath and how people wear them that’s going wrong.”

The kit outdoor guides actually wear

Guides don’t wear magic fabric. They use ordinary pieces very precisely. Most stick to a simple three‑layer idea and tweak it hour by hour.

1. A proper wicking base layer

Against the skin, they avoid cotton. Instead they choose:

- Lightweight synthetic or merino wool tops.

- Close‑fitting but not tight.

- Long sleeves they can push up on climbs.

These fabrics pull sweat off the skin so it can evaporate or move through layers, rather than pooling and then chilling you on every rest stop.

2. A breathable mid‑layer

Fleece, light insulated jackets, or active mid‑layers do the real work of warmth. Guides adjust this layer more than anything else, adding or stripping as pace and weather change. Crucially, they don’t bury heavy insulation under a fully sealed shell unless it’s truly cold and wet.

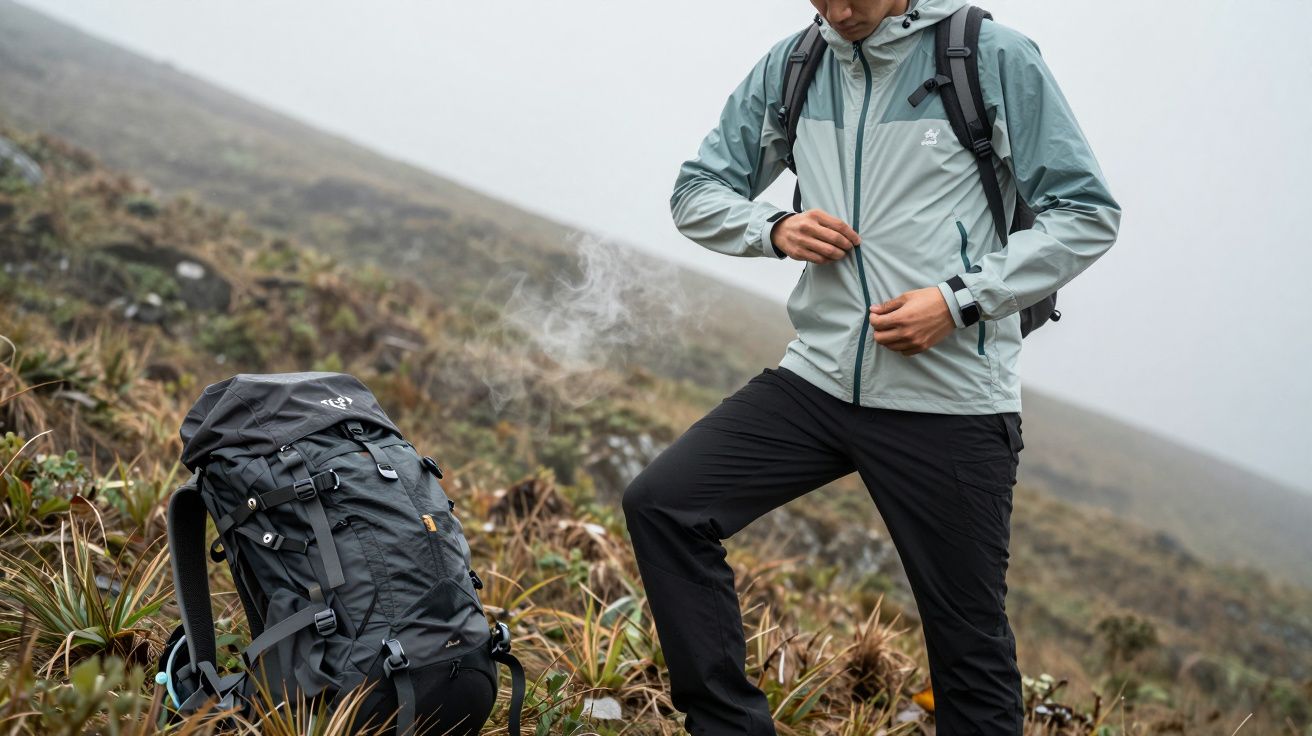

3. A shell used like a tool, not armour

The big difference is how they use their waterproof:

- It goes on late and off early – only when wind or rain demand it.

- Zips, cuffs and pit‑zips are opened often to bleed heat.

- For light drizzle or strong wind, many prefer a softshell or windproof over a full winter‑weight waterproof.

Some guides carry two shells on longer, mixed‑weather days: a light, super‑breathable “active” shell for moving, and a heavier, tougher shell for proper downpours or long, static belays.

At a glance: shell types guides rely on

| Shell type | Best for | Watch‑outs |

|---|---|---|

| Lightweight “active” hardshell | Steady hiking in changeable showers | Less durable, can feel cool when you stop |

| Softshell / wind jacket | Wind, drizzle, high‑output climbs | Not fully waterproof in heavy, prolonged rain |

| Heavy‑duty mountain hardshell | Lashing rain, winter, rough ground | Hot and steamy if worn for every mild shower |

How to wear your rain‑coat so you stay genuinely dry

You do not need an entirely new wardrobe. Small changes in timing and venting make the biggest difference.

Before you set off

- Start slightly cool. If you’re comfy at the car, you’ll likely overheat on the first hill.

- Keep the waterproof in your pack if it’s not actually raining. Use a light fleece or windproof instead.

- Swap cotton for wicking layers. Even a low‑cost synthetic running top is better than a heavy tee.

When the rain starts

Think “vent first, seal later”:

- Put the jacket on, but leave the main zip a little open at the top if wind allows.

- Open pit‑zips and loosen cuffs to let warm air escape.

- Take off your hat or push up sleeves if you’re still heating up – these small vents dump a surprising amount of warmth.

If the shower eases, guides will often unzip fully or take the shell off for the next climb, even if the ground is still wet. The goal is to avoid building a steam room around your torso.

On climbs and hard efforts

Uphill is where most people “leak”. Adjust before you sweat through:

- Strip off a mid‑layer before the big ascent, not halfway up.

- Swap to a thinner pair of gloves; hands are an easy thermostat.

- Accept a minute of faff now to avoid an hour of cold, damp discomfort later.

“Good days out come from micro‑adjustments,” says Reed. “If you’re only changing layers at lunch, you’re probably sweating too much in between.”

On summits and rest stops

As soon as you stop moving:

- Zip everything fully for a few minutes to trap warmth.

- Add a hat and a warmer mid‑layer if you’ve got one.

- Once you’re warm, crack vents again so any trapped moisture can drift out rather than condense.

That rhythm – open while working, seal while resting, then re‑open – is what keeps guides’ layers from turning swampy.

Simple layer plan you can copy

Use this as a rough script for a typical British hill day:

- Car park: Wicking base + light fleece. Waterproof in the pack. Maybe a thin windproof if it’s breezy.

- First big climb: Lose the fleece or open it wide. No waterproof unless it’s actually raining.

- Rain arrives: Waterproof on, vents open, fleece back on only if you’re getting cold.

- Summit stop: Hat on, zip everything, maybe add a warmer layer over the fleece under your shell.

- Descent: As you warm up again, start opening zips and shedding layers in reverse.

Small, frequent tweaks beat one big change you cling to for hours.

The calm after the downpour

Once you experience a hill day where you finish dry from the inside, it’s hard to go back. You stop treating your waterproof like a panic button you press at the first dark cloud, and start treating it like one part of a system. The jacket hasn’t changed; your timing has.

The rain will still come sideways. The bogs will still find your boots. But if you match what’s on your back to what your body is doing, the weather stops feeling like an enemy you have to out‑shop and starts feeling like something you can simply work with.

FAQ:

- Do I need an expensive membrane jacket to stay dry inside? Not necessarily. A well‑fitting, mid‑range waterproof plus good base layers and active venting beats a top‑end shell worn over cotton with all the zips shut.

- Why do I still get damp in merino or synthetic tops? In heavy effort you will always sweat; the goal is for that moisture to move and dry quickly, not stay clammy against your skin. A slight dampness that dries fast is normal.

- Are ponchos or umbrellas better for breathability? In steady rain on easy ground, a poncho or trekking umbrella can be very effective because they’re so open to the air. They’re less practical in high wind or rough terrain.

- How often should I re‑proof my jacket? When water stops beading on the surface and starts soaking in, wash with a technical cleaner and re‑proof. A clean, re‑treated outer fabric helps breathability as well as waterproofing.

- Is it ever OK to hike in just a base layer in light drizzle? Yes, if it’s warm, you’re moving, and you’re comfortable, it can be fine. Keep a dry layer and your shell handy and put them on before you get chilled.

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment